Why We Tell The Truth

And other thoughts on being a truthteller and wielding sharp words. Yellow Brick Road.

Why do we tell the truth?

Today, I woke up to a perfect series of tweets from dearest Dr. Thema to support this week’s newsletter on truthtelling.

We know why we maintain silence over the discomfort of truth. To spare feelings. Shame. Assimilation. Cooperation. Coping. To keep the peace in our families. To not wound our partners. To me, the reasons we don’t tell the truth are clear when so many of the systems and customs we create as society are dependent on anywhere from harmless & minuscule to violent & systemic lies. We lie in order to avoid becoming a liability to everything we know and love.

Because what people know doesn’t hurt ‘em. Because the more we know, the greater calling we possess to assume responsibility for our knowing. Because intergenerational, cultural, and systemic cyclebreakers have an obligation to create new truth entirely, but only after anchoring teensy bombs between tiny, little fragments in the faulty foundations everyone they love has placed their trust in, and deciding to hit the bright red “DETONATE" button anyway.

So, what sane person tells the truth? The big truths. I ask this honestly, because in my experience - truthtellers are not rewarded.

From my view and experience, the truthteller so often is saddled with the label of destroyer rather than the person exposing and ridding an ecosystem, family, or community of destruction. Yet, we still do it as though it’s the only way we know how to be.

Annoying Rebecca and Mean Me

Growing up, the very lassez-faire parenting style of my household rarely extended beyond trite one liners like “make good choices,” mostly because my mom was confident in my abilities to know right from wrong and believed me courageous enough to withstand the consequences of choosing the latter. She was right 9/10 times so power to those instincts.

Whenever I was too nervous or sheepish to own up to my mistakes, she would say “if you lie to me there are consequences to pay, but if you tell the truth, I will respect your honesty.” I took this to heart, deducing that the truth, as I see it and feel in my bones, always has a place regardless of how it impacts anyone including myself. Truth was always the better choice.

What I didn’t understanding yet in naïveté was that truth is complex, non-singular, non-linear. Regretfully, many of my younger selves were the kind of people who thought being brutally honest was “real” and therefore couldn’t be harmful. I extracted no joy from hurting people; I was just a young girl obsessively searching for right and wrong, and struggling to compute a social game that everyone else seemed to have a manual for in which the way to “win” was dancing around sensibilities when the truth is RIGHT! THERE!

A girl named Rebecca ate lunch with me and my friends every so often in eighth grade. We were a group of rule-abiding, homework-completing yes-ma’aming nice girls who would not dare turn anyone away who had nowhere else to sit, so we tolerated Rebecca but she was very fucking annoying. Always talking about boys at a pitch no human should reach and chewing with her mouth open. She was also a gossiper which was not really our vibe. And we talked about it. We talked about it constantly to the point that we became the gossipers we hated and were robbed of our 45 minute social hour in the cafeteria because we just couldn’t say so.

My 13 year old self believed it unkind to let a girl unknowingly annoy every human she encountered when there was still so much time to change. I didn’t like talking about people behind their backs when that information could be far more useful for the collective if told to their faces. My urge to put everyone out of their misery overcame me, so I did it. I told Rebecca that she was a gossiper and it was annoying and we all felt that way.

The next day, I approached our lunch table - the bench 13 year old girls lay unspoken claim on for the academic year. Rebecca was not there, but a kind of chill was. We all fumbled through awkward conversation for about 40 minutes and then it seemed that each one of my friends joined in a harmonious breath and narrowed their eyes on…me. “So we’ve been wanting to talk to you about this, but we think you were really mean to Rebecca.” I was stunned. “But you didn’t think we were being mean saying the same things behind her back?” I said.

“We know you mean well, but sometimes you are too honest.” I apologized begrudgingly, on the brink of tears for the following class period until the release bell rang. I sprinted home, dropping my bag at the door, and finding my mom to tell her how ridiculous it was that I was confronted by my friends for being brave enough to say what we were all thinking. I was not met with the comfort I expected, but with a question I’ve mulled over in many situations since.

“Well honey, if everyone who loves you feels the same way about you, then there must be some truth.”

A truth I hadn’t considered. How could I have missed it? I felt instant shame. Ironically, my mom was never one to withhold truth when I needed to hear it even if it was truly kicking a horse while she’s down, and I love her for it.

This was one of the earliest experiences I had in understanding the paradox of truth. It was and is true that talking behind someone’s back is mean. It is also true that saying certain things to someone’s face can be really mean regardless of how honest it is and the discernment to know when to deploy truth exists in something the “data” cannot account for. We account for that in empathy and love. And that is how we learn the power of wielding something that cuts right to the core of our being.

While thinking in black and white - truth or lies - I missed the gray often in my youth. I still do now. My conviction toward truthtelling could inflict just as much, if not more, harm without considering why and how it needed to be told. I’m sure there were a million ways I could have addressed annoyance without hurting Rebecca’s feelings, and I’m also certain we all would’ve been just fine had it never been addressed at all. But I ultimately decided to tell the truth because carrying lies and trading honesty in gossip rather than authentically expressing myself became too heavy. I do believe living transparently is living light even if lonely and unpopular, which is incentive to do it.

As for my mom’s advice, majority opinion is not always truth - just use American presidential elections as an example - but provides a lot of data about where a group of people is inclined to seek collective truth at any given time and that is important.

Obviously, there are is a sliding scale of risk and return for every kind of truth we tell. There are small truths with limited shock like telling your friend she’s annoying only to find out you’re mean. There are big truths like declaring to the world that the earth is round when everyone believes it’s flat and being labeled unhinged. There are biggish, smallish truths that feel huge, like going to therapy for the first time to discover much of what occurred in your childhood was in fact not okay, only to bring it up at every family gathering and being met with backlash that suggests you are what is not okay. This is a mindfuck, and it requires emotional and mental fortitude to lead the charge for truth by yourself. I wonder how much of that fortitude is in our constitution, something we’re born with, and how much of it can be built by exercise and practicing truth the way we do love. Love is as love does and so is truth.

Wielding Swords

In family units, the truthteller becomes black sheep. In even the purest communities, truthtellers are often ostracized and isolated as harmful until proven otherwise. Is the ability to tell the truth - against consensus, all perceived backlash, consequence or unlikely reward - a trait of resilience? Disobedience? Courage? Control?

The grit to speak truth even when you know it will land on closed ears or resentful hearts is certainly resilient and courageous. Tap dancing on a fragile foundation your entire existence relies on is disobedient. And grasping to hold one, singular, and omnipotent truth is a function of control. But I don’t think any of these motivators are powerful enough to drive a person to pursue truth and its obstacles for a lifetime.

Our natural, god (little g to fit whatever you call infinite reality) given impulse to tell the truth is represented by the Ace of Swords in the tarot. In the Pamela Colman Smith illustration, the sword of truth is presented by divine source in the form of a suspended hand, slashes through a cloud of confusion and mystified stories to set the record straight. I take the crowned sword to represent the noble act of providing clarity. The wreath symbolizing victory.

You can’t just wave around a sharp object in a room full of soft bodies. Before learning to wield the sword of truth we view our circumstances as relatively black and white, which often leads to not-so-victorious outcomes. The gentle and compassionate power of the sword rests in our discernment - our ability to identify that many strong perceptions of right and wrong exist including our own, another’s and the collective’s Within this discernment includes the tried and true questions - does it need to be said? does it need to be said by me? does it need to be said right now? And perhaps most importantly, am I willing to be burned in the process lighting the match of truth?

The distance between what needs and needn’t be the said is the distance between data and knowledge. Data is our black and white - x is true so must be qualified by words and behavior at all times. But knowledge. Knowledge accounts for the gray, the many truths that exist in the very same quarrel, attraction, and conversation making our reactions to the very same triggers, art, and romance wildly different from another’s. These collective realities can’t be reduced to what is seen because of what remains softwired in our hearts rounding out the harsh edges of data and creating knowledge. The human instinct to protect.

Psychotherapist Esther Perel says the impulse to tell our truth, our story, is about protection (listen to podcast linked above STAT), about our love for each other. As we become truthtellers, our parents and grandparents and siblings may think the omission of bits and careful curation of our history - what happened to our people and their people and their people - will beget a truth that protects our hearts and ability to imagine beyond trying, violent, or seemingly impossible circumstances. We maintain a web of secrets to have something to fall back on.

We can’t possibly say this is “wrong” when our brains facilitate fabrication of history for us naturally. I can’t remember enter years of my life because my brain wanted me to have the capacity to dream beyond trauma. There is something instinctual here. In the minds of our family and society members who have endured traumatic events, fractured bonds, detoured paths and respond with revision, truthtellers are a threat to the ability to dream beyond those circumstances and at risk of extinguishing a brighter future and a stronger connection to each other.

On the other hand, truthtellers understand that nobody will be able to validate truths they haven’t identified for themselves yet, or may never care to identify for protective reasons. Still, we believe that imagination and connectedness and protection can all still exist when nobody’s experience is omitted.

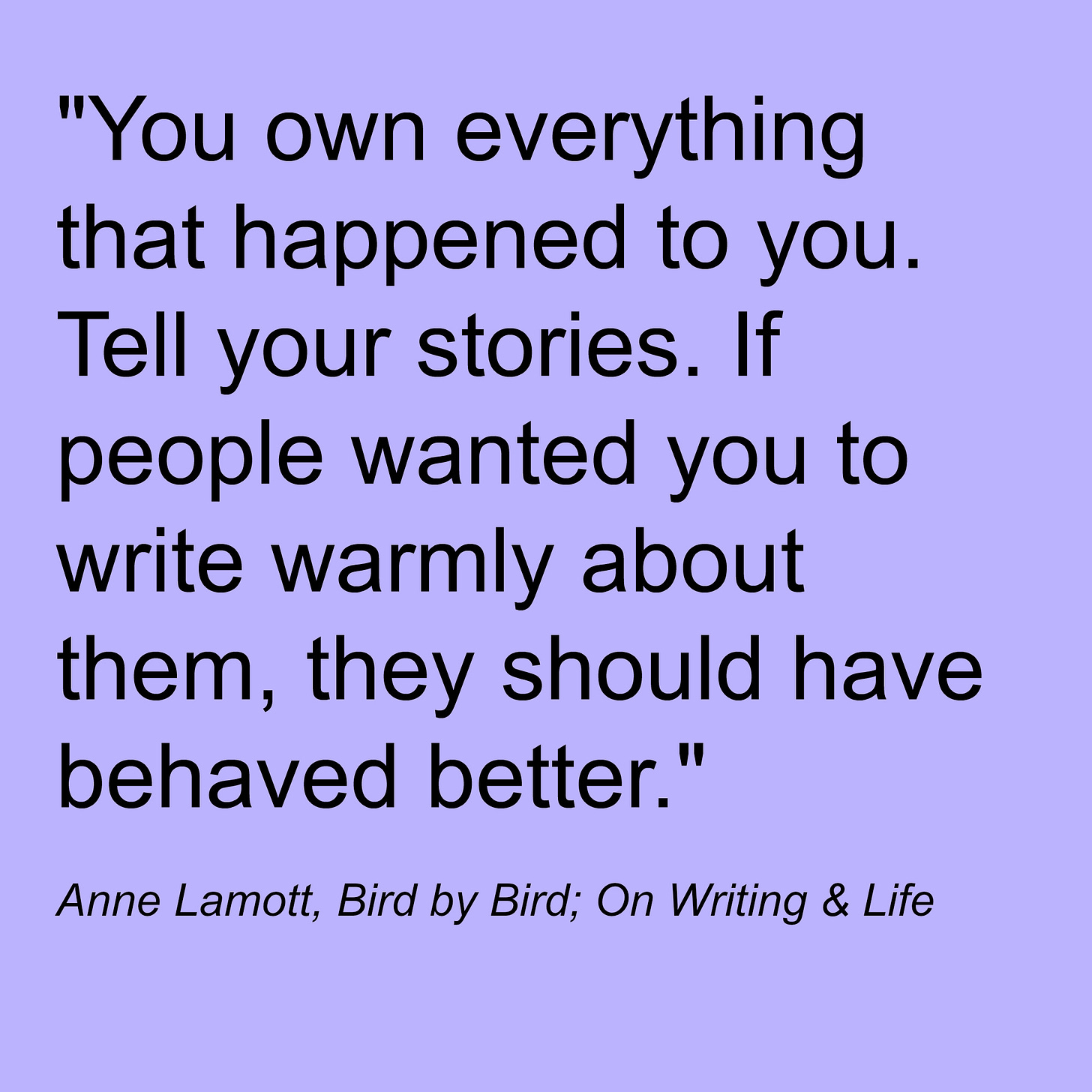

I’ve been working on a book of personal narrative storytelling, as you find right here on this newsletter. Anyone who has written memoir or personal stories understands the shedding, grieving, release, and tension that comes with sharing your truth for the public and realizing it has never and will never exist in isolation. We live with, around, and through the truths of anyone who exists in our stories - friends, family, relatives, partners, flings, and enemies. The pursuit of truthtelling is hard because the creation and output of those stories is just more powerful and healing than concealing them for someone else’s interest.

This book feels really important to me for obvious reasons. It feels really important to the people who will hopefully read it someday in the near-ish future too. But there are people like my own mother and my siblings and my estranged father and friends and exes and all kinds of people from distant lives for whom I am neither responsible nor qualified to tell alternate truths. Many of them will not be happy or in agreement with everything that is written.

Naming my trauma publicly - just as it happens privately - will not be understood as anything other than harmful by those who played strong hand in creating it, and even endured it with me from their own perspective, not ready to name it themselves. I have to be satisfied with bringing form to my stories regardless. As a person whose purpose involves truthtelling in the form of personal narrative, I have to let my work sometimes be perceived as the truths nobody needed to say - just as I was once satisfied doing when calling little Rebecca annoying at the lunch table.

Sometimes, the truthteller in us has to win over the person in us. I have no interest in cruelty, exaggeration or the final say as a person might be, but I have an insatiable need to understand why I am the way I am and why so many people can relate and why personal traumas and joy become collective traumas and joys and why the hell it matters as a practitioner of truth does. I have this voice that has been inside me for as long as I remember, reminding me that the reason I tell the truth is just to say that I was here. I felt this and thought this and loved this at some point and I really, really hope I’m not alone. I do this to connect.

Esther Perel calls stories - what we consider to be truthful enough to be spoken - “data with a soul.” I believe, at our core, we tell the truth sheerly as a marker of our existence and our history. To mend the severed stories that so many of our histories have been subject to through division, war, subjugation, oppression, and cycles of interpersonal violence. When we tell “the truth,” we grow roots as foundation for all else we build our lives. To some extent, we risk complacency, stubbornness, and building the proverbial hill to die on when we decide truth from a scarce and fear-based reality. To another, we give ourselves an opportunity to revere and rewrite the stories of our people.

Ultimately, I have reason to believe that truth is mutable and fluid, perhaps even a bit evasive. The truth always lends room for growth, to be a different person 2 minutes from now than you are while reading this. As our complex understandings of how the world works and why it matters shift, so does our desire to exercise truth as a way to extend “bids for connection” toward those we suspect feel similarly. If we lie to be concealed and isolated, we tell truth to find acceptance. If we lie to avoid shame, we tell truth to face and dispel it. But people can only meet you as deeply as they’ve met themselves, and there is a fine line between self-deception and external deception until there isn’t. Until lying to ourselves prevents us from connecting. From loving.

I think in our humanness, we cannot always guarantee anyone or anything will stay with us so we ultimately tell truth because being ourselves right now is the only thing may have for certain. Maybe the only truth is the fire of change - ripping through control and complacency and codependency - and we mislabel what we wish to keep as “truth” about ourselves, our lives, so we don’t have to send it to the embers. To be transmuted into a more healed, open, and honest way of life that we don’t have a name and control manuals for yet, which is the scariest.

This was so so SO good! I need to read it again because it touched on so many points. My experience with telling the truth has also been traumatic. In one particular incidence, I told the truth to a powerful person (my former boss) and in the process I lost someone I considered a friend -- because they chose to be loyal and protect their career. For a year I could not get over it. But now I’m at peace with it. I take responsibility for HOW I told the truth, and not for telling it. And I’m much more cautious about telling the truth because it is a double edged sword. THANK YOU for this lovely essay ❤️